Making Something Wild & True

Felt artist Kristina Foley on working in dialogue with the living world

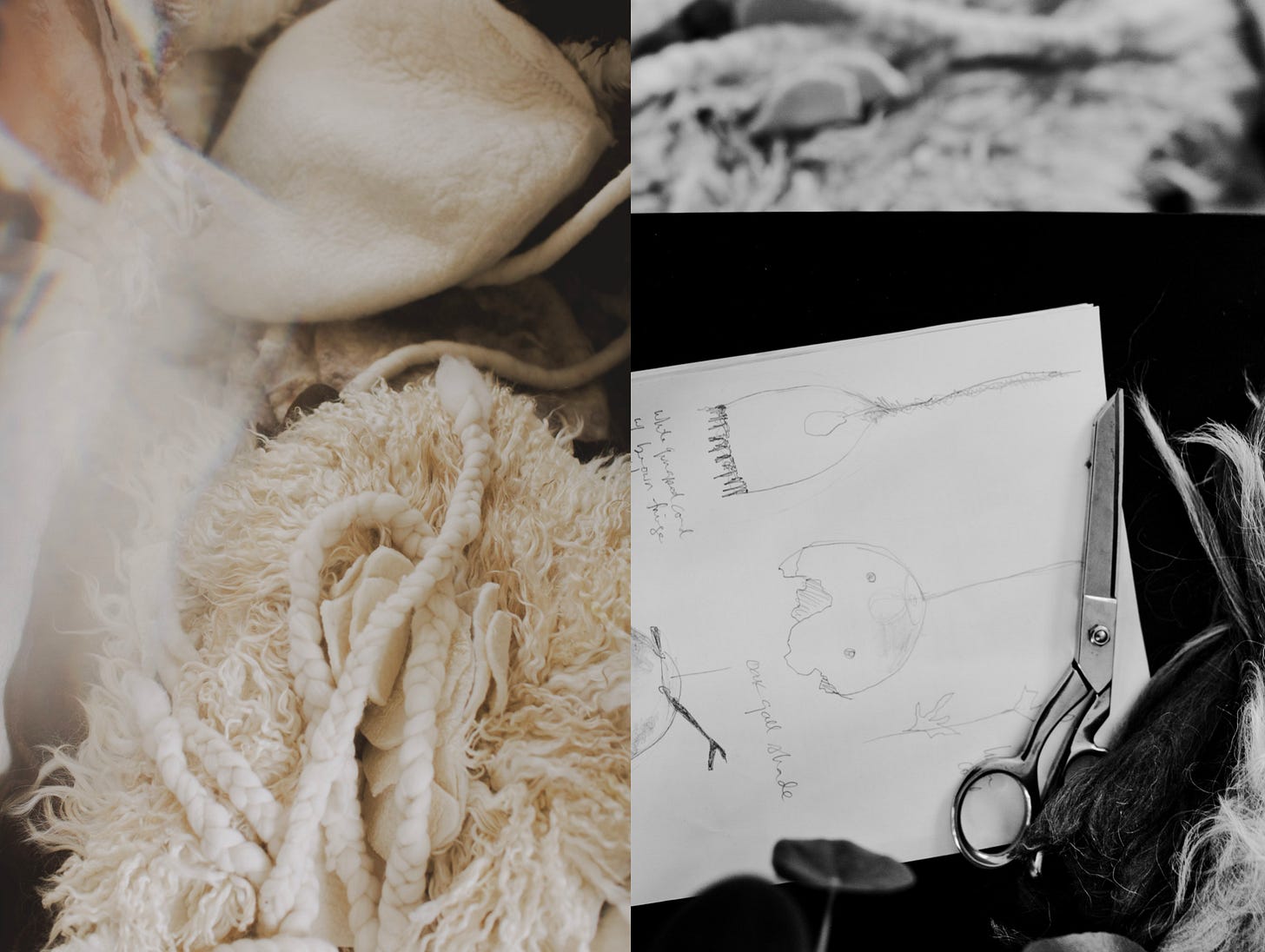

In Kristina Foley’s hands, wool becomes something more than material…it becomes memory, transformation, belonging. And through the slow, tactile ritual of felting, she calls forth the latent beauty embedded in the raw and the overlooked: sheep’s wool, local dye plants, the fibers of a place.

This summer at Antica Terra, we’re excited to share that Kristina’s work will unfurl into the landscape itself as a series of woolen lamps, each hand-felted from the fleece of our vineyard’s sheep and installed above the Table in the Trees like luminous markers of the land’s own memory.

We spoke with Kristina in a Beauty School conversation on the alchemy of felting, the patience of process, and the what that emerges when we let material lead.

What initially drew you to working with wool as a material and a language?

Wool is a material that emits an earthy quality, and tracing it back leads you to its place of origin, the animal, and the land itself. There is a deep familiarity in connecting with a material that has been a part of human life since the domestication of sheep over 10,000 years ago.

Feltmaking has always held a pleasurable sense of mystery for me. The process is relatively simple but transformative: in agitating wool fibers with warm water and soap, the fibers interlock and become something entirely new. It feels magical, alchemical, and offers infinite paths of exploration.

The visual lexicon of felted wool spans from ethereal, spiderweb-like delicacy to dense, stone-like solidity; it can envelop and interact in unexpected ways when combined with materials like wire, plastic, wood, cloth, and other fibers; and can produce zero-waste forms, vessels or garments with no sewing required. Wool naturally occurs in a range of sophisticated colors and textures, each with unique possibilities for mark-making. It also readily absorbs botanical color when dyed and takes on deep, vibrant hues. On top of all that, it is an inherently technical, high-performance material: water-repellent, fire-resistant, insulating, strong, and fully biodegradable.

In both Italy and now the Pacific Northwest, you've worked closely with local materials. How has this localized approach shaped your sense of belonging or community?

Nature has always been a doorway for me and given me a deep sense of belonging, no matter where I am in the world. It connects me to the land, its people, and myself. I’m fascinated by working with materials in their most raw form, from locally-sourced wool to dye plants I grow in my garden. I have relationships with farms across Oregon where I visit and select fleeces for each project, and I value the community and activism that comes from supporting small businesses and mills as we work together to re-establish a domestic natural fiber industry. I like to discover what is revealed when the global supply chain and shipping industry are stripped away, and I look at what’s around me with fresh eyes. What might seem like a constraint becomes a boon.

In 2026, I plan to spend a few months in Sardinia collaborating with artists and advocates from both the Slow Food and textile communities to help build the Italian Fibershed…and to explore the regional wool of la pecora sarda, the Sardinian sheep.

Feltmaking seems to require being present with the material rather than imposing rigid expectations. How do you maintain openness to what the wool wants to become?

It’s a process that cannot be rushed. There is a pace and rhythm required when agitating the fibers that involves an element of time for it to become a coherent material. There’s also a certain unpredictability when the wool meets water. My role is to mediate this encounter, drawing on my experience with both the material and the process. I prepare the fiber, the design and technical process as carefully as I can, and then leave space for the unknown to enter.

No matter how many times I repeat this process, it remains humbling. Even in moments of uncertainty, I work to let the materials express their wildness and resist the urge to over-edit.

Your work represents a commitment to slow, tactile processes. Have you found that working with wool has taught you anything about patience, or slowing down in other areas of your life?

I’ve been learning to shape my creative process into a kind of ritual that brings both my mind and body into the present moment. It’s helped me to understand the value of any activity that allows me to enter a flow state. That can be gardening, cooking, spending time in nature…things that engage all my senses and ground me.

Beauty School explores how beauty can be found at all levels, from the grand to the minute. What are some small details or moments in the process of working with wool that you find particularly or unexpectedly beautiful?

I recently had the opportunity to hold a freshly shorn fleece while I was helping at Nightsong Farm in Corbett, OR. The fleece was so light in my arms as I carried it to the skirting table; it was still warm, carrying the scent of the animal and the field. It filled me with a sense of excitement, stirring my imagination about what it might become.

In contrast, at the end of feltmaking, I have a piece of wet, compressed wool, and it’s often hard to tell what the result will be once it’s dry. Looking at it, I see all the ways things didn’t go according to plan and I can imagine the post-production work that will be required. It can feel discouraging, especially after the physically demanding felting process. However, stepping away and returning to a piece after it has dried often reveals a beautiful outcome that I couldn’t have predicted.

After years of immersion in Italy's artisanal culture, how do you think about honoring traditional techniques while still making work that feels relevant to the moment?

The very nature of craft is that it has endured through millennia, passed down from human to human through our hands and words. Form, function, and aesthetics have been honed through repetition. In Italy, there is a deep respect and role for the artisan in society; the quality of one's craft is expected to be exceptional.

Craft and art are intertwined: the master painter knows how to grind and mix pigments, the sculptor travels to the quarry to select the stone. Italians are curious, innovative, and discourse-driven. In Tuscany, a farmer selling radicchio at the market has as much to say about the philosophy of living and making as a highly educated designer, and the two will often enjoy exchanging ideas.

Living and working in this culture for over a decade impacted the quality of my craft. It gave me thicker skin and a better sense of humor. Most importantly, it imparted the mental spaciousness, creativity, and value that comes from living in a place where the artist is an integral part of society.

How do you think about your work and the ways it visibly reinforces our connections to animals and how they impact our experience of a place and our relationship with the living world?

Felted wool invites the attention of all our senses, transporting us into the natural world at the root of its making: it is at once wild like nature and cultured, shaped by centuries of tradition.

Nature has a way of bringing us back to ourselves. It helps quiet the noise and opens up an exploratory and symbolic space; creatures do that in an instant. It’s one of their gifts. I want each piece to carry the raw beauty of the wool, infused with the energy and spirit of the animal.

Thank you to Kristina for sharing a bit of your wisdom with us. You can see her pieces on-site this summer as part of our ongoing art programming at Antica Terra, and learn more about Kristina’s work on her website and on Instagram.

All photos by Making Dept.